Did you know there's a good chance some of your favorite songs were written by people you've never heard of? It's true. From Elvis Presley to Garth Brooks, many of the biggest songs from the biggest artists ever came from people you couldn't differentiate in the Starbucks line.

Videos by Wide Open Country

That thought may be a little jarring for some. The song that got you through a bad breakup, or that you danced to at your wedding, wasn't really the genius of George Strait, but actually a guy named Dean Dillon (who wrote nearly 60 George Strait songs, along with classics such as "Tennessee Whiskey").

But of course, these classic songs require the perfect translator. Which is why George Strait can take somebody else's heart and soul and bring it to life with his own performance. When the right singer performs the right song, magic happens.

It's like the saying goes: "It takes a village to raise a child." That same mentality applies to music. The amount of people it takes to really make an artist successful can be staggering. But no matter what, it always starts with the songwriter.

The Life of a Song

Now, plenty of huge songs came straight from the artist themselves. A song can have many different paths. The most simple is when an artist write the tune themselves, then records and releases it. Often, an artist writes the song with somebody else (a member of the band, or a different songwriter) and then records and releases it. Still a fairly simple process.

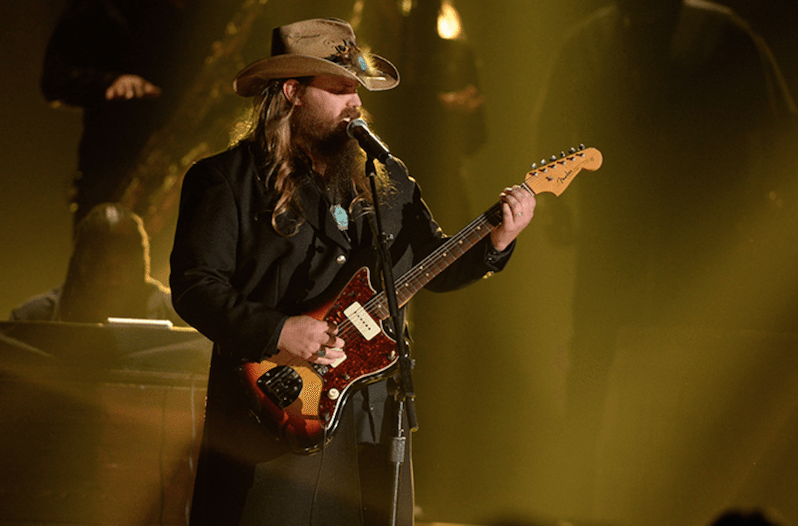

But in country and pop music in particular, a song's path to success takes many other twists and turns. And, in many cases, artists first see success by writing songs for other people. Chris Stapleton is a great example of this. Before he exploded on the scene as an artist, Stapleton spent 14 years writing songs other people made famous. He wrote tunes like Luke Bryan's "Drink A Beer," Thomas Rhett's "Crash And Burn" and Josh Turner's "Your Man."

So when you see somebody like Stapleton finally get his own chance in the spotlight, he already had much of Music City rooting for him. Also, here's an important distinction. When we say somebody "wrote" a song, more often than not it means the wrote the song with somebody else. So, for instance, Stapleton wrote "Drink A Beer" with a guy named Jim Beavers (who also wrote Stapleton's song "Parachute" with him).

Songwriters often get to wear different hats. They serve the song, which means they get to write in many different styles.

The Tried-and-True Publishing Deal

The vast majority of country songwriters start out with a publishing deal. Of course, there are exceptions to the rule (Shane McAnally, for one), but here's what that means.

Songwriter Sally has some great songs. She's been in town for awhile and made friends she likes to write with. She also starts playing those songs out at some songwriter rounds around town, which means she gets on stage with a few other people and take turns playing songs acoustically.

Eventually somebody in town wants to introduce Sally to a publisher. So Sally goes and meets with Pete's Publishing company, and Pete decides he wants to sign Sally to a publishing deal. That means Pete agrees to pay Sally what's called a "draw" or "advance." Usually, that's somewhere between $25,000 and $50,000 per year. In other words, just enough to allow Sally to only write songs and not worry about a different job. But here's the rub: that money is essentially a loan, not a salary.

Pete's Publishing also agrees to help set up co-writes for Sally so that she and other great writers (either from the same publishing company or another one) can get together and write songs. And Pete also promises to send Sally's songs to artists and try to get them recorded.

In exchange, Pete's Publishing takes a percentage of how much that song makes. This can get really complicated, but let's just keep it simple and say Pete takes all of Sally's publishing rights, which is equivalent to 50% of the song. So if Sally wrote a song that makes $1,000, she makes $500 and Pete makes $500. But that's only after Pete recoups the advance he paid Sally back.

Demos, Holds and Cuts

Alright, so how does Kenny Chesney hear Sally's song? After she writes the tune, she'll probably do a quick "work tape" of the tune, which basically means record it on her phone. And sometimes that's all it takes. But usually, writers want to "demo" the song.

A demo is a version of the song that usually has the basic elements (drums, guitars, vocals etc.) but doesn't have all the bells and whistles of a fully produced song. Demos can range in price, but it's safe to say a fair amount fall between the $500 and $1,000 range and take a day to do. If Sally doesn't want to sing on the demo, she can hire demo singers (and other musicians) to come jam it out quickly. Sometimes Sally has to pay for the demo, sometimes its her publisher Pete. It just depends on the contract.

So Sally sends the demo to Pete, who just loves it. And it turns out, Kenny Chesney is looking for songs. How do we know? Because Chesney's team listed him on what's called a "tip sheet" or "pitch sheet." It consists of a few lines of text with the most basic info — who the artist is, the label, producer, project and preferred method of receiving song submissions. Or, sometimes, if they have a good relationship with Pete, the artist's team might call him directly and ask if he has any songs he's excited about. (There are also independent "song pluggers," who independent writers pay to help get their songs into the right hands).

Now let's say Kenny listens to Sally's song and loves it. He puts a "hold" on the song, meaning nobody else can record the song until he decides if he wants it to go on the album or not. Usually this period only lasts a few weeks. If all goes well, they go in and record the song, and Sally officially gets to call it a "cut."

Sometimes this part can be particularly stressful for a writer. For instance, the song "Whatever She's Got" by Jimmy Robbins and Jon Nite went through several different "holds" before finally landing at David Nail, who eventually took it to No. 1.

Caitlyn Smith has an amazing song about being a songwriter called "This Town Is Killing Me."

How Much Do They Make?

Not enough, usually. There are several different ways songwriters get paid, though. In the most simple terms, the songwriter and publisher split 9.1 cents every time a song gets downloaded or manufactured on CD. So if an artist makes 1,000 copies of a CD with your song on it, they owe you $91. If they sell 1,000 digital downloads of your song, they owe you $91.

That's not a whole lot of money, considering the decline in sales. If your song goes gold (selling 500,000), which is a huge success, it's still only $45,500. You'd have to have a song do that every year to be just under middle class in America. Songwriters also get a small payment every time their song gets performed on the road.

What about streaming? Oy. Streaming royalty rates are extremely complicated (as are radio royalty rates). But in the interest of being overly simple, songwriters can expect to make about $4,000 per 1 million streams on Spotify. So if Sally gave away her publishing in her deal with Pete's Publishing, she's getting $2,000 per 1 million Spotify streams.

Which makes radio important. Because terrestrial radio still builds houses for some songwriters. If you get lucky enough to get 100,000 or more spins on radio, your check will have weight to it. Otherwise, it comes down to quantity for most songwriters.

The Digital Revolution

So how does the way people consume music affect songwriters? Well, on the one hand, it doesn't. Songwriters continue to write with the hopes of getting songs heard. No matter if its on tour or on Spotify.

But the changes to the music industry affect everybody. And the scary part is that many of the payment contracts come as negotiations between companies and organizations. Which means songwriters usually don't get a place at the table. And it means sometimes labels can hide how much a song actually makes.

So right now, songwriters need help from Congress. Copyright laws are woefully outdated. Songwriters rarely get a place at the table when it comes to establishing royalty rates. There is a lot of money in music. But songwriters unfortunately often get the short end of the stick.

But without songwriters, we wouldn't have some of the world's most amazing songs. And, for that matter, some of the world's most amazing artists who sang them. So support your local songwriters. And take a moment to research who wrote some of your favorites. The answer just might surprise you.