For most Americans, the booms and busts of the oil industry are little more than a number on a sign at the gas station. But entire towns live and die by the ebbs and flows of the gasoline pipeline. When oil is struck, the ensuing gold rush upends quiet lives as companies scramble for a piece. In many ways, things change for the better. Barren cafés and shops spring to life. Signs boast six-figure salaries for entry-level positions. But with this newfound prosperity comes a downside. Gorgeous natural environments are threatened. Rents skyrocket, and schools become overcrowded. As the "man camps" of roughnecks increase, so too do prostitution and sex trafficking. Finally, when the boom goes bust, these bustling communities are reduced to ghost towns.

Videos by Wide Open Country

Texas Monthly's Christian Wallace examines the effects of the oil boom on West Texas in the podcast "Boomtown." In the 12-chapter audio documentary, Wallace "follows characters along every rung of the oil field ladder, from the executive cutting billion-dollar deals to the itinerant pipeline worker risking life and limb, and from the traveling exotic dancer following the trail of money to those who worry that our planet is on a path to destruction."

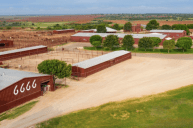

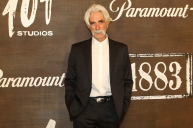

The Texans portrayed in "Boomtown" serve as the subject of an upcoming television series from "Yellowstone" co-creator Taylor Sheridan. In "Land Man," the sleepy boroughs turned meccas turned ghost towns become the backdrop for Sheridan's brand of primetime soap, which stars Billy Bob Thornton as a crisis manager for an oil company presumably facing one of these catastrophic busts. With Wallace on board as an executive producer, the series promises an authentic look at life in the Permian Basin. Plot details for "Land Man" remain largely under wraps, but here's what Wallace uncovered in "Boomtown" and, by extension, what we can expect to see when the television series airs.

The Economics of Oil in the Permian Basin

Pgiam/Getty Images

In the 1970s, two geopolitical factors contributed to the oil boom in the Permian Basin, the most prolific oil site in the nation (via Texas Monthly). In 1973, the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC) placed an embargo on the U.S. in retaliation for its support of the Israeli military. And in 1979, the Iranian Revolution tied up U.S. oil imports. These two events worked in confluence to create a massive oil crisis. Cars sat in mile-long lines at gas pumps as panicked consumers vied for a drop. The demand for homegrown oil in the U.S. skyrocketed — and drillers in West Texas were more than happy to rise to the occasion.

President Jimmy Carter encouraged the drilling by deregulating the price of American oil, and companies big and small flocked to the region. By 1981, the number of rigs in the U.S. had nearly doubled. Oilers were raking in the money. So were the towns, whose shops, restaurants and strip clubs embraced the newcomers with open arms.

In Houston, the population grew 40% — even as most cities in the U.S. were shrinking. The skyline tripled in size, and the rich got a lot richer. Restaurants began tossing their pasta with caviar. Texans wore gold Rolexes, which they called "Texas Timexes." And they drove two-seater Mercedes-Benzes, which they called "Midland Mustangs" and typically featured a bumper sticker that said something like "Drive 80 — Freeze a Yankee in the Dark" — a vengeful jab at the East Coast elites who were suffering from the energy crisis.

Most of the profits went back into the ground: more wells, more oil. Everyone was getting rich — and then everything went to hell.

So much oil was being produced that the industry went bust. As the oil supply grew to overwhelming heights, the prices plummeted. And so, too, did the number of rigs, which dropped from 4,500 to only 663 by the summer of 1986. As oilers fled the Permian Basin, town populations dwindled. Once-bustling streets became deserted, and eerie West Texas ghost towns became the norm.

A very different bumper sticker began to pop up: "Please God, give me one more oil boom," it pleaded. "I promise not to piss it away."

The Current Fracking Boom: Will History Repeat Itself?

HHakim/Getty Images

The rise of fracking technology has ushered in a new oil boom in the Permian Basin. Are West Texans destined for another bust? Or have they learned their lesson this time around?

Wallace was born in the region in 1988 and grew up in the shadow of the last major bust. He describes how few people in his hometown had steady work, though vestiges of the boom era remained: the minor league baseball team was called the Midland RockHounds, a nickname for geologists who hunt for crude oil. He'd hear wistful stories about the good times when oil and money flowed freely.

But in 2012, while he was away at college, he heard about a new boom happening back home. A horizontal drilling technique known as fracking enabled drillers to tap previously inaccessible oil trapped in shale. When he returned in the late 2010s, he stepped into a world completely different from the one he'd left.

Signs of prosperity were everywhere. There were long lines at all the stores. A barbershop claimed that its barbers were making up to $180,000 per year. At a dealership, expensive pickup trucks and even private planes were lined up and ready to be sold.

The threat of another bust always looms. However, there's reason to believe that this boom will be different.

According to NPR, investors are now demanding that oil companies share profits with them instead of immediately investing those profits into more drilling. This prevents an oversupply of oil, which is what caused the bust in the '80s. The industry is still growing — but now it's growing at a far more gradual rate.

"Investors are actually demanding ... more discipline from these shale producers," says Angie Gildea, the head of U.S. energy for global accounting firm KPMG. "They want return of dividends and cash back to shareholders versus prioritizing just growing production."