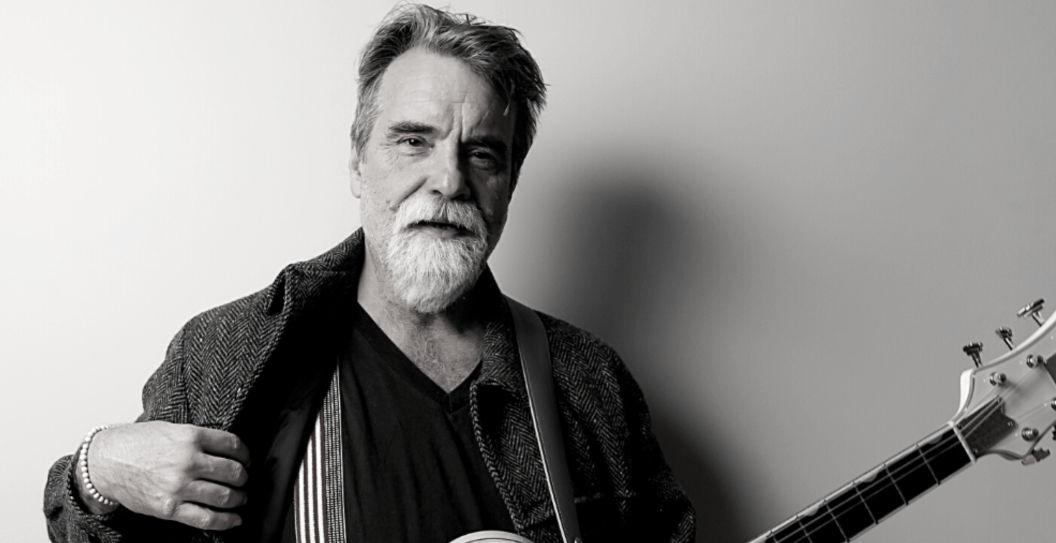

There's not much that Darrell Scott hasn't done in his last three decades as a working musician and songwriter. But for his new album, Old Cane Back Rocker, he discovered a new approach to making an album.

Videos by Wide Open Country

For the first time ever, the "You'll Never Leave Harlan Alive" songwriter and his bluegrass band — bassist Bryn Davies, mandolinist Matt Flinner and fiddler Shad Cobb — recorded during a three-day span on the road, between gigs in Arkansas and Colorado that saw the group settle in Louisville. However, it wasn't Louisville in Scott's native Kentucky but, rather, a suburb of Boulder in the Centennial State where the band got into a groove at eTown Studio.

The circumstances allowed the group to become grounded for a few days while they recorded, even though they were far from home — in turn giving the project the energy of a live album despite it being captured in a studio setting.

"The norm is to come home between [shows] because it's actually more expensive to stay out there together," Scott tells Wide Open Country of his decision to record while out on the road. "But if you do stay out there, why not make something beautiful that you can use out of it? That's where this recording came in."

Old Cane Back Rocker also marks the Darrell Scott String Band's first studio record together. Collectively, the group is still a seasoned bunch, having played on and off together for close to a decade in addition to previously being captured together on 2017's Live at the Station Inn. According to Scott, he's long wanted to record a proper album with the bunch and thought there was no better time to do so than when they're already on the road and hitting their stride from gigging together.

"I wanted us to sing harmony and make the record with all hands on deck instead of using background singers and session players like I have in the past," says Scott. "It forced us to take one more step forward toward being a more cohesive band."

That cohesion can be heard throughout the album, from the harmonies on songs such as "Charlie and Ruby" and "Banjo In The Holler" to hard-driving instrumentals including "Fried Taters" and "Raji's Romp." Further proof lies within the lead track "Kentucky Morning," which tells the Scott family's story of northern migration away from Kentucky to more stable work in steel mills and on assembly lines up North. Told from the viewpoint of family whose love for Kentucky kept them from leaving for good, the song is just ambiguous enough for listeners to easily place their own narratives in it — a balance most songwriters strive to find but very few can — thanks to lyrics such as:

"And I was there with my brother making factory pay

But Lord my soul was alone

And it was four in the morning I shut down my machine

And I told them: 'I'm going home.'"

Scott further leans into his Kentucky narrative with the album's cover art, which features a picture he took of his cousin, Dwight Messer, during a walk last winter on their family property in southeastern Kentucky. The shot is a simple but stoic image of Messer — a member of Scott's family who didn't move North — standing in front of his now-abandoned childhood home. It conveys a blue-collar grit and humble way of living that the region, and Scott, have become known for in its songwriting.

"Kentucky is so much a part of my history and background," says Scott. "This instrumentation (and some of these songs) comes from a Kentucky state of mind, so I thought having that picture I took was a good fit for the cover."

A similar down-to-earth sensibility can be felt on "Charlie and Ruby," an enduring love story that Scott wrote about his neighbors of the same names upon him first moving to the Nashville area in 1992. Written from the perspective of him watching the couple's relationship play out over time through his window, the song illustrates how not even a lack of children or financial stability could come between the high school sweethearts — emphasizing how family and relationships are the true source of wealth, not material objects, in the process.

While Scott's new originals garnered the bulk of attention — and rightfully so — a couple choice covers also found their way into the record's rotation, including Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young's "Southern Cross" and his father Wayne Scott's "This Weary Way." In the case of "Southern Cross," Scott says he was drawn to the song's harmonies along with wanting to use the opportunity of having John Cowan recording on it to make it an homage to the bluegrass and reggae ways of New Grass Revival.

Regarding his process for deciding which covers to play and record, Scott says, "It doesn't even have to be a giant lyrical awakening; it can come from a groove or great solo, too.

"I also need to feel like I can do something with the song that's worth doing. I don't want to just waste four or five minutes with it on a record. Pete Seeger once said that if you want to become a good writer, learn 1,000 songs from other people. I love doing covers; I just want to do them in a way that feels different and honest to where I want to go with it."

One song that's not quite a cover, but which Scott reinvents nonetheless on Old Cane Back Rocker, is "It's A Great Day To Be Alive." Originally recorded for his debut album Aloha From Nashville in 1997 before being recorded by Travis Tritt in 2000, the new version of the song features a slowed-down bluegrass orientation with a heavy, thumping bass line to go with Scott's unwavering charm.

According to Scott, the redone version of the song was recorded as a single in 2017 after he found out about a cornfield near Nashville that was designing an image of him into one of its corn mazes, even going so far as to press the song title into its sea of maize. This led Scott and his son to travel to the site and film a music video of the song that splices together performance and drone footage that further help recast the timeless song for a new generation of listeners.

"It's funny — it's almost like I'm covering myself," says Scott. "I'm not singing it the way I did back in 1994. I didn't want to be static about it; I wanted to treat it differently nearly 30 years later."

A lot has changed in music and the world at large since Scott moved to Music City and penned "It's A Great Day To Be Alive" in the '90s, but you won't hear him griping about it. He says he's more comfortable in his own skin than he's ever been. That has given him the confidence to experiment and push the boundaries of his music, such as recording this album with a bluegrass frame of mind or implementing everything from distorted guitars to aggressive drums, string quintets and horn sections — all of which he's planning to do in the future.

"I feel that my job is to be honest through all of these giant shifts and changes, which is easier now than when I first started out," says Scott. "I never want to get bogged down thinking my next record needs to sound like my last. That'd be like Picasso staying in the Blue Period the entire time he was creating art. It's laughable."

READ MORE: Tyler Childers' New Music Video Has the Internet in Tears