You've probably heard of Leah Chase, even if you're not from New Orleans, or from the American South. The heralded Cresent City chef, known as "the Queen of Creole Cuisine," has received numerous accolades for her decades of work in the culinary, arts, and civil rights spheres. Among these are lifetime achievement awards from both the James Beard Foundation and the Southern Foodways Alliance, the University of New Orleans Entrepreneurship Award, and myriad awards from the NAACP. Leah Chase is best known as an exceptional Creole chef and keeper of the gumbo z'herbes at Dooky Chase's, but the impact she made in ninety-six years extends far beyond the realm of her kitchen, and far beyond the city of New Orleans.

Videos by Wide Open Country

As Chase once said, "Everybody likes a bowl of gumbo. I like to think we changed the course of America in this restaurant over a bowl of gumbo."

Jazz and Sandwiches

Born in New Orleans, Louisiana in the winter of 1923, Leah Chase spent her early childhood living in rural Madisonville and helping her family run their strawberry farm. However, as the local area high schools did not allow Black children to attend, she returned to New Orleans after finishing sixth grade, living with an aunt throughout high school. After graduation, Chase immediately began working at the since-shuttered Colonial Restaurant on Chartres Street and other French Quarter dining rooms.

Dooky Chase Restaurant

In 1946, Chase met and married local musician Edgar "Dooky" Chase II, whose band was playing at a Mardi Gras ball. At age eighteen, Dooky was already revered for his sixteen-piece "transitional swing to modern jazz" band, which featured his sister, Doris Chase, as a vocalist.

Beginning in 1939, the Chase family owned and operated a sandwich shop and lottery ticket outlet that quickly transitioned into a beloved bar, known as Dooky Chase's restaurant. Located in Treme—one of the nation's earliest African American neighborhoods—Leah Chase began working in the po-boy restaurant which had since moved into the Chase family's shotgun house. Over the years, Leah Chase would take on many positions at the restaurant—that of hostess, decorator, and chef—transforming the space from a cherished local spot to a nationally recognized outpost of New Orleans' cuisine.

The Queen of Creole Cuisine

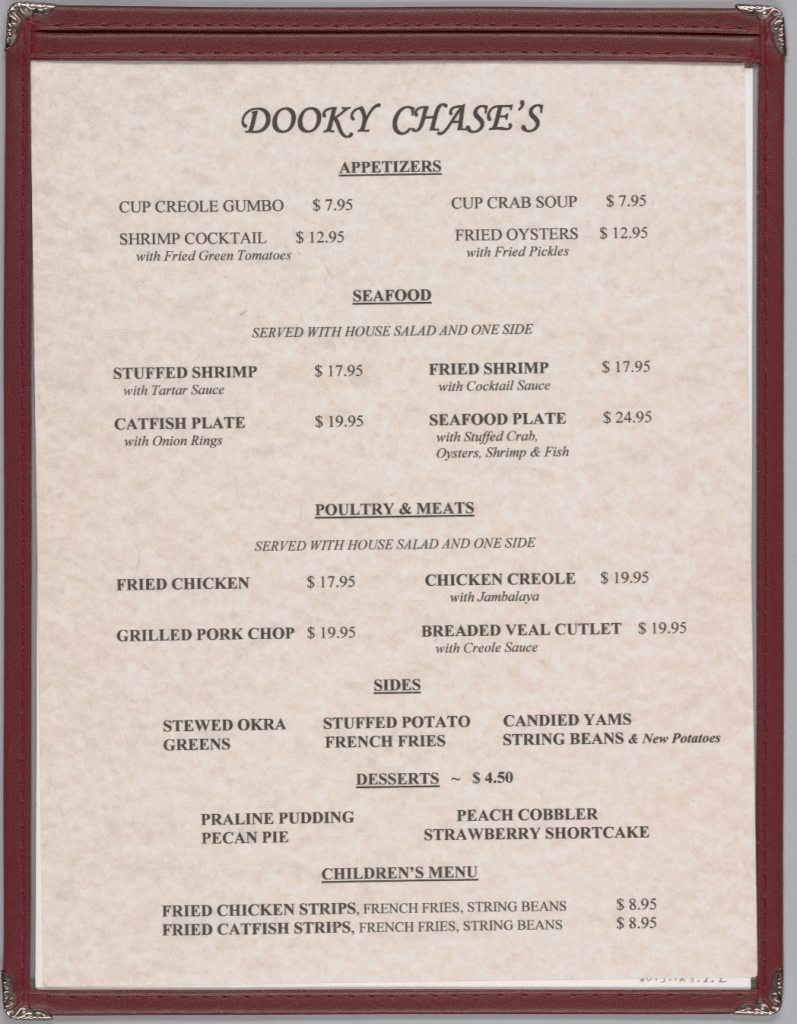

After taking over the kitchen at Dooky Chase's restaurant, Chase began mastering recipes more common at the segregated restaurants in town, like the decadent Shrimp Clemenceau. That dish and others like it were often served at the famed Galatoire's, a French-Creole establishment revered by the wealthy, white establishment of New Orleans. According to the New Yorker, Chase's diners were initially perplexed "by the butter sauces and accents aigu." But that quickly began to change: "When integration came in, you saw how other people did things—turns out there's nothing wrong with shrimp Newberg," she said.

As Leah Chase expanded the restaurant's menu with a new culinary vision, the barroom and po-boy shop transformed into a sit-down restaurant, introducing one of the first fine dining restaurants in the country exclusively oriented towards the local African-American community. Mariam Ortiqe, Revius Ortique, Jr.'s widow, the first Black justice elected to the Louisiana Supreme Court, told the New Yorker that Dooky Chase's "was the only white-tablecloth restaurant for Black people."

Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of Dooky Chase's Restaurant and Chef Leah Chase

But Leah Chase's community ethos expanded far beyond her menu and decorations: Beginning in the 1950s, Dooky Chase's Restaurant became a safe meeting place for both national and local civil rights leaders. Although local ordinances prohibited interracial gatherings, as early as 1955 the dining room transformed into a meeting place to plan the Godchaux Sugar Reinary Strike. This tradition would continue throughout the next few decades, becoming a secret meeting location for organizers such as the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Freedom Bus Riders during the 1960s.

A homemade pipe bomb exploded in front of the restaurant in 1965, sending shards of metal flying into the dining room. But Chase never let the actions of others, however violent, deter her from her course. As she told the Times-Picayune in 2013, "I always say, I'm going to be just like this old gospel song. I'm going to be on this battlefield till the day I die."

"Mr. Obama, you don't put hot sauce in my gumbo."

(EMMANUEL DUNAND/AFP via Getty Images)

Although the space was forced to close following Hurricane Katrina in 2005, Dooky Chase's Restaurant remained a national icon, continuing to attract famous visitors and wide acclaim was they reopened two years later. When Barack Obama visited in 2008, Chase reprimanded the then-presidential candidate for adding hot sauce to her gumbo. As she later recalled, she had to tell him, "Mr. Obama, you don't put hot sauce in my gumbo." She attended to each customer with great care, even when normal folks were dining beside the likes of Ray Charles or Louis Armstrong.

Although most would visit for Chase's exceptional Creole cuisine and the welcoming atmosphere, Leah Chase also committed herself to feature African American art on the walls of her restaurant. Through this endeavor, Dooky Chase's became the first gallery for Black artists to be showcased in New Orleans.

Dooky Chase's Today

Today, Dooky Chase's remains a New Orleans stalwart, although there is one day revered in the restaurant above all else: Holy Thursday. While it is perhaps most well-known for its Creole gumbo, on Holy Thursday (the Thursday between Palm Sunday and Easter) the restaurant suspends its normal menu of red beans, rice, and smothered porks chops to serve Chase's famous gumbo z'herbes, fried chicken, and cornbread—a specialty of the matriarch's.

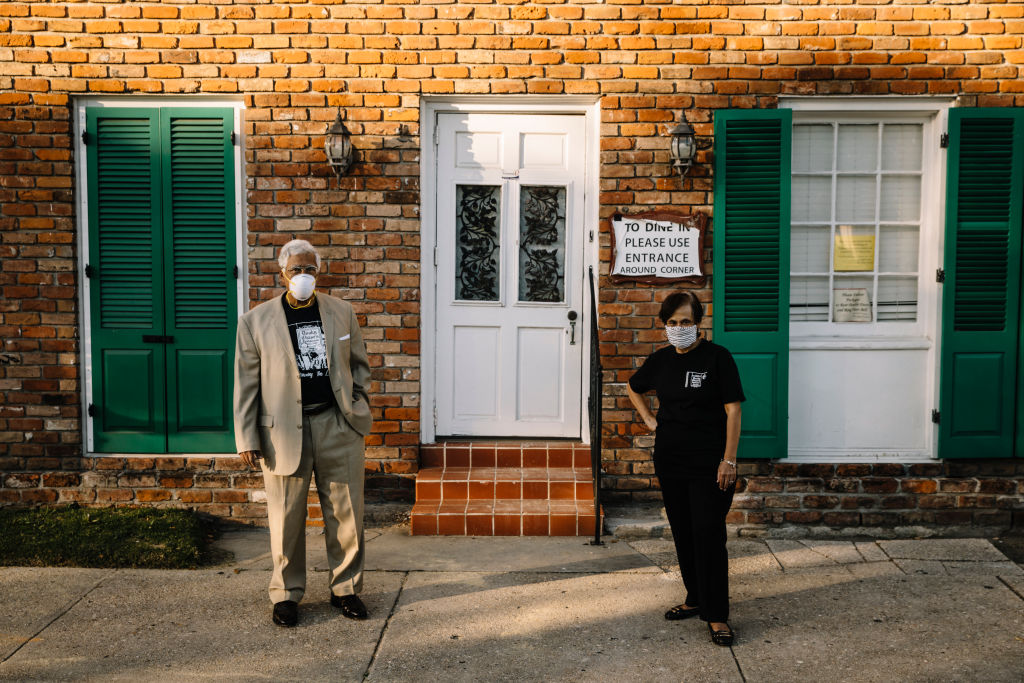

Edgar Chase III (L) and his sister Stella Chase Reese (William Widmer for The Washington Post via Getty Images)

Chef Leah Chase remained in the kitchen of Dooky Chase's Restaurant until her death in 2019. Her advocacy work continues to thrive under the helm of the Chase Family Foundation, which advocates for education, the visual and culinary arts, and social justice causes. And although she's no longer making the gumbo herself, the restaurant remains family-owned and operated to this day. If you would like to visit, they are currently offering both dine-in and take-out options for diners. It's almost mardi gras season, after all.

READ MORE: Boudin King Cake is a Sweet and Savory Louisiana Specialty