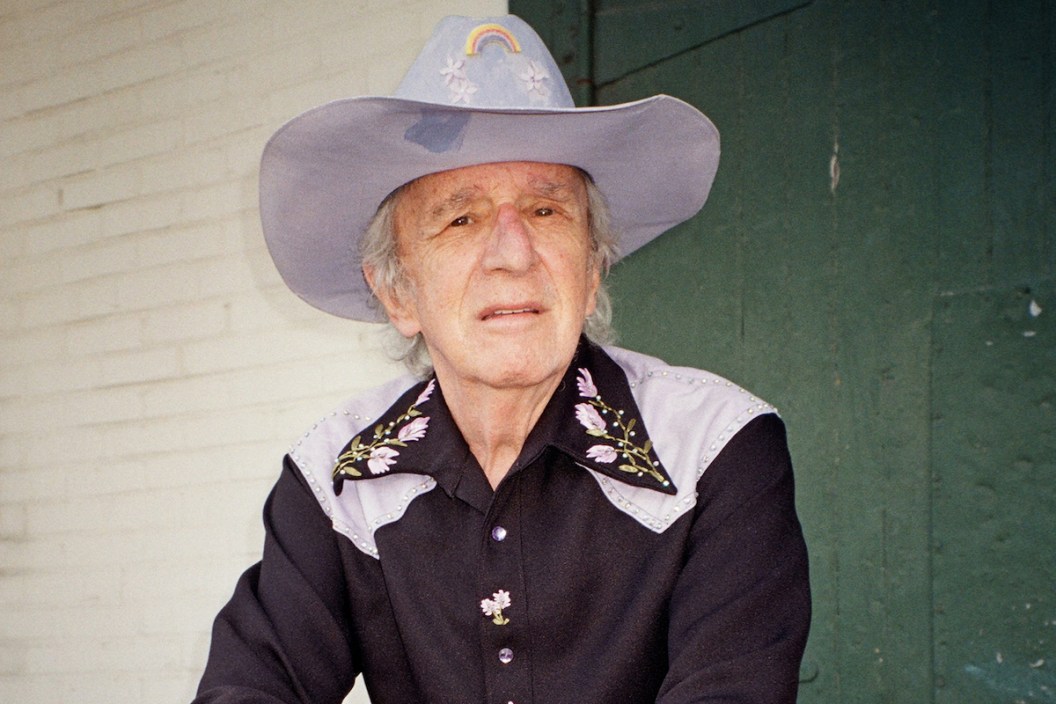

[dropcap]O[/dropcap]ver 50 years ago, gay country pioneer Patrick Haggerty chose honest self-expression over dishonest pursuit of country music trends.

Videos by Wide Open Country

"I have a certain amount of talent and stage talent," Haggerty told Wide Open Country. "I'm not particularly gorgeous, but so what? I can write a good lyric, and I can get on stage and I can put on a good performance. I've always been able to do that from the time I was 5 years old and my aunts put me on a picnic table and had me sing 'Cruising Down the River.' I knew that I could do that, and I could have in 1970 gone to Nashville and gone into the closet and pursued a career in country music and stayed in the closet and maybe made a mark that way. I certainly had the motivation to do that, and part of me wanted to do that. But I had to make a very stark choice in the early '70s about who I was and how I wanted to live my life. I couldn't be a queer, Marxist country music star. I could be a queer Marxist or pursue being a country music star, but I couldn't be all of those things at the same time. That was out of the question."

Haggerty lived his truth as a member of Lavender Country: the Seattle band that in 1973 released the first gay country album, thematically speaking. Though its original run of 1,000 copies soundtracked key moments in the gay liberation movement for peers in the Pacific Northwest, the album's lack of wider-spread traction seemed to back up Haggerty's assumption about the limited reach of queer, Marxist country music.

"When I made Lavender Country, I was like poison," he explained. "Nobody would associate with me, and I mean nobody. I mean it was to the point where I had to go do something else with the rest of my life because I was untouchable. I knew that would happen when I made the album. I wasn't stupid."

Lavender Country broke up in 1976, with Haggerty moving on to other forms of activism. Though Haggerty returned to music in the early 21st century with multiple projects (a brief Lavender Country reunion in 2000 included), he at no point pushed to get his flowers now.

"I didn't have anything to do with Lavender Country's recent rise to prominence," he said. "I wasn't thinking about it. I wasn't jockeying myself into position. I wasn't talking to anybody about anything about having Lavender Country be anything but dead. I was happy enough with my life with Lavender Country being dead. I had made peace with it decades ago. But the culture changed."

Over the past decade, the fringes of the music business —fortified by punk rock and welcoming of country outsiders— have championed Lavender Country's self-titled album. A key domino fell when the song "Cryin' These Cocksucking Tears" gained traction on YouTube among seekers of lo-fi rarities. That surprise momentum resulted in reissue label Paradise of Bachelors making Lavender Country widely available on vinyl in 2013.

Since then, everything from modern ballet performances in San Francisco inspired by Lavender Country to collaborations with famous fans Trixie Mattel, Mya Byrne and Orville Peck spread Haggerty's unchanged political message to an eager audience.

"You all caught up with it, and frankly, Lavender Country is a very useful device artistically in terms of the fight against fascism," Haggerty added. "People are using it for that reason, and that's what it is for. It took 50 years, but now it's been made into an elegant tool for the very reason that I made it in the first place. It doesn't get better than that."

In the first half of 2022 alone, Lavender Country's platform grew even more, between punk imprint Don Giovanni Records' wider release of the band's second album, Blackberry Rose (first issued independently in 2019 as Blackberry Rose and Other Songs and Sorrows), the unveiling of the group's first-ever music video (for "I Can't Shake the Stranger Out of You") and a package tour with a revolving cast of young artists inspired by Haggerty: Paisley Fields, Austin Lucas, Lizzie No, Jett Holden and Mali Obomsawin.

"I would love to do collaborations with older country music people, and some of them I love," Haggerty said. "Sometimes, it's difficult for some of them to love me. So, I work with whoever puts themselves in front of me and wants to work with me. It does tend to be a younger crowd but not exclusively. It's not anything I sought after myself. It's just who's there. The younger set is more politically in tune to who I am and what I'm doing."

At each tour stop, Haggerty joined three tour mates and a full band for song-swapping interspersed with captivating stage banter by someone who's role in the fight for LGBTQ+ rights dates back to the Stonewall era of the late 1960s.

"There are many things that are powerful about [Haggerty's] politics," Lucas said. "He and I don't necessarily have entirely 100 percent the same politics. The overarching theme that encompasses both of our politics is the desire to ensure that we are empowering and uplifting as many other people as possible. If we can do that through the medium of music, then that's absolutely fantastic. I don't think there's that many people on planet Earth who are capable of making everyone feel quite so welcome as Patrick Haggerty is. To me, that's the magic of Patrick Haggerty."

"[Haggerty] really cares about class struggle, and he cares about politics more than anything else," Fields added. "He uses music as a vehicle to get his message out as far as his politics. He'll be the first to say he's a screaming Marxist bitch."

Haggerty kicks down walls by leaving the stage by sets' end along with his bandmates and sparking a full-on dance party amid everyone in attendance— a practice that hilariously forced Byrne to invest in a longer bass cable for shows with Lavender Country.

"The standard format for putting on shows is to put you onstage," Haggerty said. "Of course, there's reasons people are on stages. It's mostly to give everyone a wider visibility. But it separates you from your audience, and it teaches your audience that you're not really one of them. That you're elevated from them, that you're more important to them. It feeds into the whole star thing. It's not who I am, and it's not what I aspire to be. I'm here to support the working class. So, when you get down into the audience, you're able to look them in the eye and dance with them and pass the microphone back and forth. It's an equalizer."

The resurgence of Haggerty's music career opened doors for others to firmly choose what they consider the right side of history, such as St. Louis-based singer-songwriter and former Lavender Country tourmate Ryan Koenig.

"I said, 'Well Ryan, I can't pay you to go on tour with me. I'm not making that kind of money. And you're going to pay a price for being seen with me. It's going to impact your career,'" Haggerty explained. "He said, 'I don't care about the money. I just want to go on tour with you.' He's screamingly talented, and you'd be an idiot to say no. He's not gay. He's married, and his wife [Kellie Everett] is a very prominent musician. So, I'm getting to know Ryan a little better [on the road], and I said to Ryan: 'Okay, look, it's time to get real. What the hell are you doing, and why are you riding down the road with me for no money? What's going on?' He said, 'I do love you and I do love your music, but that's not what I'm doing. I'm not doing this to participate in politics. This is a career move on my part. I'm doing this for selfish reasons to advance my own career. I want my fanbase to know that I'm not a white supremacist, and I want my fanbase to know that I'm not some sort of proto-fascist. And I don't want white supremacists and proto-fascists at my concerts. I can't think of a quicker way to put that message out to my fanbase than to announce that I'm doing a tour with you.'"

Without doing anything different socially or musically from Lavender Country's original intent, Haggerty finds himself in a role he deemed impossible to achieve in the early '70s.

"It may have taken 50 years, but guess what: I got the last laugh because at this point I say humbly and without aspiring to it that I am a country music notable," he said. "More and more people are acknowledging that's the truth. I ended up being wrong. I get to be an extremely queer, Marxist country music notable anyway. That's who I am these days, so ha ha! I got you in the end, so I'm having fun with that because I ended up with the whole enchilada."