Linda Martell made history in August 1969 when she became the first African American woman to perform on the Grand Ole Opry. That long overdue change by the Mother Church is just one of many discussion points about an artist who, like so many others to grace the Ryman or Opry House stage, relished the opportunity to add her own voice to a genre she loved as a child.

Videos by Wide Open Country

Fast-forward to 2022, and an increased focus by journalists and academics on country music's Black roots plus a Maren Morris namedrop at the 2020 CMA Awards has netted Martell a fraction of the credit she's long deserved.

To quench others' curiosity and tell a family story the right way, Martell's granddaughter, Marquita Thompson, has started a GoFundMe campaign to finish a documentary about a country music trailblazer.

"My family and I are working on a documentary film on Linda Martell the artist, her experience as a Black woman singing Country music, an almost completely white space at the time of her debut, a time where people who looked like her were fighting for the right to simply sit down to eat at restaurant to enjoy a meal," Thompson wrote in the campaign description. "A documentary that gives a closer look into who she was/is outside of Country music, a more honest take on why she was overlooked during her short lived career and the likely reasons for the sudden influx of attention she's received in the past 3-4 years. This documentary has been in the making for nearly two years and I've realized that if we are going to ensure her story is heard in her words, we're going to need more resources."

As of Feb. 17, 2022, the campaign has eclipsed its original $25,000 goal, thanks in large part to a $5,000 donation by Morris and $10,000 credited to CMT Viacom CBS. Thompson has since expanded her goal to $100,000.

Thompson has since shared a teaser of the film, featuring clips from an interview with a leading voice in country music journalism, Andrea Williams.

Y?all know I?ve been working on this document about my grandmother, right?

Well, here?s a teaser of some of what we?ve been working on.

I hope y?all enjoy!

Official trailer coming soon! #TheLindaMartellStory pic.twitter.com/AIbtgY4QPf

— Quia ?Very Rich Millionaire? Tarantino (@QuiaTarantino) February 17, 2022

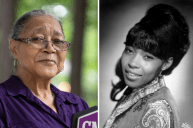

Linda Martell

Country singer Linda Martell poses for a portrait circa 1969 in Nashville, Tennessee (Photo by Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images)

The Leesville, S.C. native's Opry debut coincided with the release of her first two singles, "Color Him Father" and "Before the Next Teardrop Falls." Although they cracked the country chart's Top 40 for Martell, both songs performed even better when cut by other artists. "Color Him Father" songwriter Richard Lewis Spencer won a Grammy for his band The Winston's 1969 recording. In 1975, one of the greatest talents to ever waltz across Texas, Freddy Fender, made "Before the Next Teardrop Falls" into a county staple.

Others' successes aside, a lifetime of experience prepared Martell (born Thelma Bynem) to make the most of her short stay in the Nashville spotlight. Before she became a groundbreaking country music singer, Martell performed with three of her brothers in a gospel quartet. She also cut a couple of pop records in the early 1960s with the Anglos (sometimes spelled "Angelos").

Per the National Museum of African American Music, during a performance at Charleston Air Force Base, officers encouraged Martell to mix some country songs into her set. The crowd reaction that night led Martell to devote her career to a musical style she used to hear her father sing around the house.

"I guess that's all we knew," she told Hollis L. Engley of Gannett News Service in 1998. "'Your Cheatin' Heart' and "I'm Walking the Floor Over You.' Until we got into our teens, we knew country music. That was it."

Martell's big break came when she inked a deal with Shelby Singleton's Plantation Records, the label behind Jeannie C. Riley's crossover hit "Harper Valley PTA." Plantation issued Martell's lone country album, 1970's Color Me Country, plus two additional singles, "Bad Case of the Blues" and "You're Crying Boy, Crying." The album and its singles strike a balance between the classic country of Ernest Tubb and Hank Williams ("I Almost Called Your Name") and the folk-grounded story-songs then prominent outside of Nashville ("Tender Leaves of Love," "San Francisco is a Lonely Town").

Aside from her Plantation Records output, Martell cut at least one single ("Love Has a Way" b/w "Mama Stay Home") for Nashville's less-than-reputable Delta Records.

Between 1969 and the mid-'70s, Martell appeared on the Opry stage 11 more times. For comparison, Carly Pearce (deservedly) notched 75 appearances in a similar span (March 2015- June 2020). That's not a complaint about Pearce or an attempt to pit one woman's career highs against another's (and data on more than two artists' appearances in a five-year span would be necessary to know if 12 appearances is a little or 75 appearances is a lot, comparatively). Still, it's a reminder that even with today's women facing disadvantages within country music, some current artists' opportunities seem bountiful compared to those of Martell.

Read More: Dona Mason, Rissi Palmer and an Inexcusable 20-Year Gap on the Country Charts

At least one journalist saw Martell's Opry opportunities and record label affiliation as stepping stones toward a lengthy career.

"Charley Pride has hit the big time as a country and Western singer, and Linda Martell has all the talent to make it just as big on the distaff side," wrote the St. Petersburg Times' Chick Ober in 1971.

Ober projecting Martell as a long-term star in 1971 makes sense. Aside from her already-mentioned professional highs, she was fresh off 1970 appearances on The Bill Anderson Show and Hee Haw. But for whatever reason, she never cut another big-label single, much less scored another minor chart hit.

Per Engles' 1998 article, Martell persevered as an entertainer for around 20 years, with her father's 1990 death bringing her back to South Carolina to take care of her mother and drive buses for children and the elderly.

"Everywhere I went I was accepted with all of the entertainers and the producers," Martell told Engles about her years as a country artist. "They were great. Now, with audiences you always got that few out there that's going to call names. But you just can't let it get you down."

Martell has resurfaced at least once in the 21st century. On a Jan. 22, 2014 episode of Swedish TV series Jills Veranda-- Nashville, its hosts traveled to South Carolina to discover that Martell could still sing the old, sad songs with the best of them.

Over 50 years later, Martell should be remembered as two things: the first Black woman to perform on the Grand Ole Opry and a gifted vocalist with a small yet rewarding discography that deserves attention aside from necessary discussions about race issues and gender identities within country music.

This story originally ran on June 9, 2020. It was updated on Feb. 17, 2021.