What we lost in Chef Sam Kang we gained in biscuits and molecular gastronomy. This week's Quickfire was yet another examination of the chefs doing something many of them simply do not know how to do: make a Top Chef-level complete dish that includes a biscuit. Some chefs did great—in the top were Chefs Evelyn, Damarr, and Jackson; the latter won—while Chefs Buddha, Jae, and Ashleigh were in the bottom. Interestingly, there was no immunity offered for this win.

Videos by Wide Open Country

The Quickest Top Chef 19 Episode 4 Recap

James Beard Award-winning and Michelin-starred chef Wylie Dufresne joined the judges for this week's Elimination Challenge, which had a deceptively simple premise: in 2-person teams, make two dishes that look exactly the same, but taste completely different. Chef Dufresne prepared a sample pairing for the chefs to taste and analyze. Quickfire winner Chef Jackson and his chosen partner, Chef Buddha, received an extra 30 minutes of cook time.

(l-r) Robert Hernandez, Sarah Welch -- (Photo by: David Moir/Bravo)

Almost every pair of contestants blew this challenge out of the water. Chefs Ashleigh and Luke came in on top, winning universal praise from the judges for their scallop and compressed honeydew dish, the colors and textures of which matched exactly their king oyster mushroom and pickled cucumber dish. But Chefs Jackson and Buddha won with their sensational everything-but-the-bagel savory dish, which looked exactly like their strawberries and cream dish. In the bottom were Chefs Jo and Evelyn, whose pork belly dish looked similar to their cheesecake dish, but neither tasted good, and Chefs Robert and Sarah—whose combo of a shrimp sausage terrine and a strawberry panna cotta looked a tad alike, but neither achieved ideal texture or flavor—were both eliminated.

TLDR Stats

Quickfire Winner: Chef Jackson

Elimination Challenge Winner: Chef Jackson, Chef Buddha

Eliminated: Chef Robert, Chef Sarah

Hot Biscuits & Lucille's Houston

The Quickfire Challenge's guest judge was Chris Williams, the owner of Lucille's, a legendary Houston restaurant built and operated in the name of the owner's grandmother, Lucille Bishop Smith. Born in 1892, Smith graduated from Huston-Tillotson University in, possibly, 1912 (the exact year is unknown), and married Ulysses Samuel Smith, whom she met in college. Ulysses eventually earned the title of the "Barbecue King of the Southwest."

Chris Williams

The first African-American businesswoman in Texas, Lucille Smith invented the first commercially produced and sold hot roll mix, became the first black woman to join the Fort Worth Chamber of Commerce, and was even a teacher-coordinator for vocational service programs in the Fort Worth Independent School District. According to Texas historian Carol Roark, Smith realized that there were very few professional paths for black women interested in the culinary arts. As a result, during her employment at what is now known as Prairie View A&M University, Smith crafted one of the earliest college commercial food & technology programs—essentially a post-high school version of the program she was in charge of in Fort Worth ISD.

Langdon Manor Books

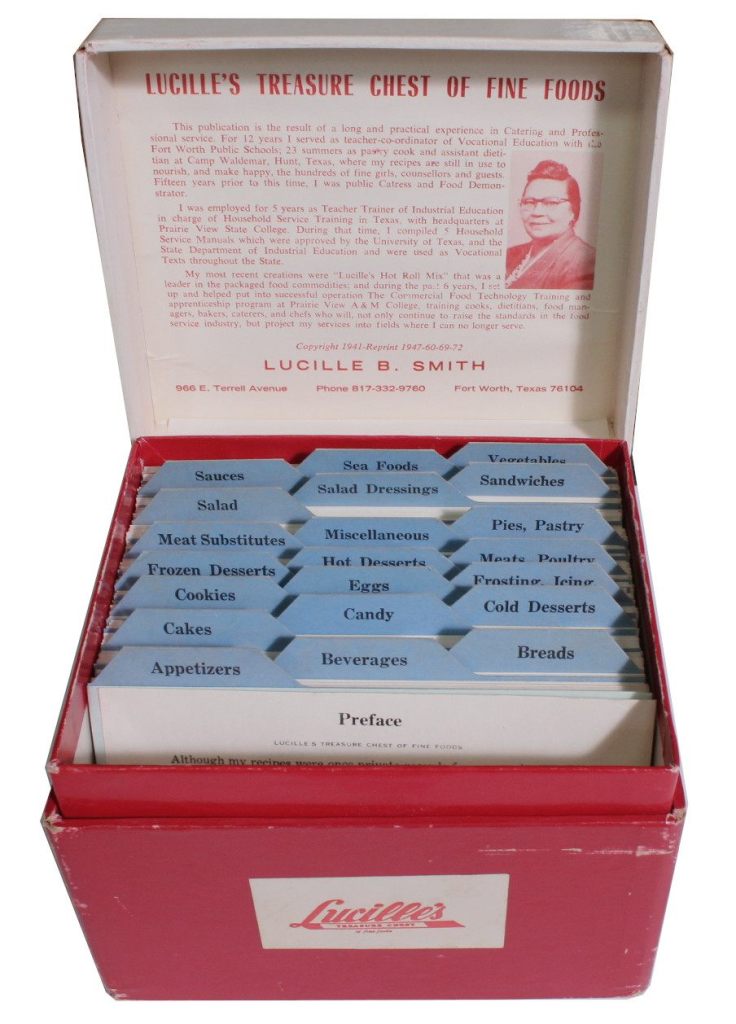

In 1941 Smith published her first cookbook, Lucille's Treasure Chest of Fine Foods. Though the book was reprinted multiple times, today a copy is very difficult to find and is considered a prized collectible. What I find most interesting is how varied the cookbook's categories are: there's eggs, candy, beverages, and appetizers, there's also sections for meat substitutes, "sea foods," and an entire section devoted just to frosting and icing. A copy of the cookbook is stored in the University of Texas at Austin's library; a second copy resides at Southern Methodist University in Dallas. While it's not known how, if at all, the recipes were altered in successive reprints of the cookbook, the volume does feature Southern classics, including hominy casserole, hush puppies, and spoonbread, but also more inventive takes on Southern cuisine, including banana flake salad and potato fudge.

Throughout her career, Smith continued to cook. Her famous chili biscuits used her own "Lucille's All Purpose Hot Roll Mix." The phenomenal popularity of the mix led to, by spring of 1948, grocery store sales of 200 14-ounce boxes per week! Her first month's profits, which came to $800, were donated immediately to St. Andrew's Methodist Church in Fort Worth. Besides the 21 products that could be made with the mix, Smith also marketed her invention using accolades she'd won, including having the chili biscuits served on American Airlines flights, and even in the White House under President (and fellow Texan) Lyndon B. Johnson.

Courtesy Fort Worth Star-Telegram Collection, Special Collections, The University of Texas at Arlington Libraries

The biscuits weren't the only reason LBJ was an admirer of Smith's; as a thank you for her baking and sending Christmas fruitcakes to Fort Worth-area servicemen in Vietnam, President Johnson sent her a handwritten thank you note.

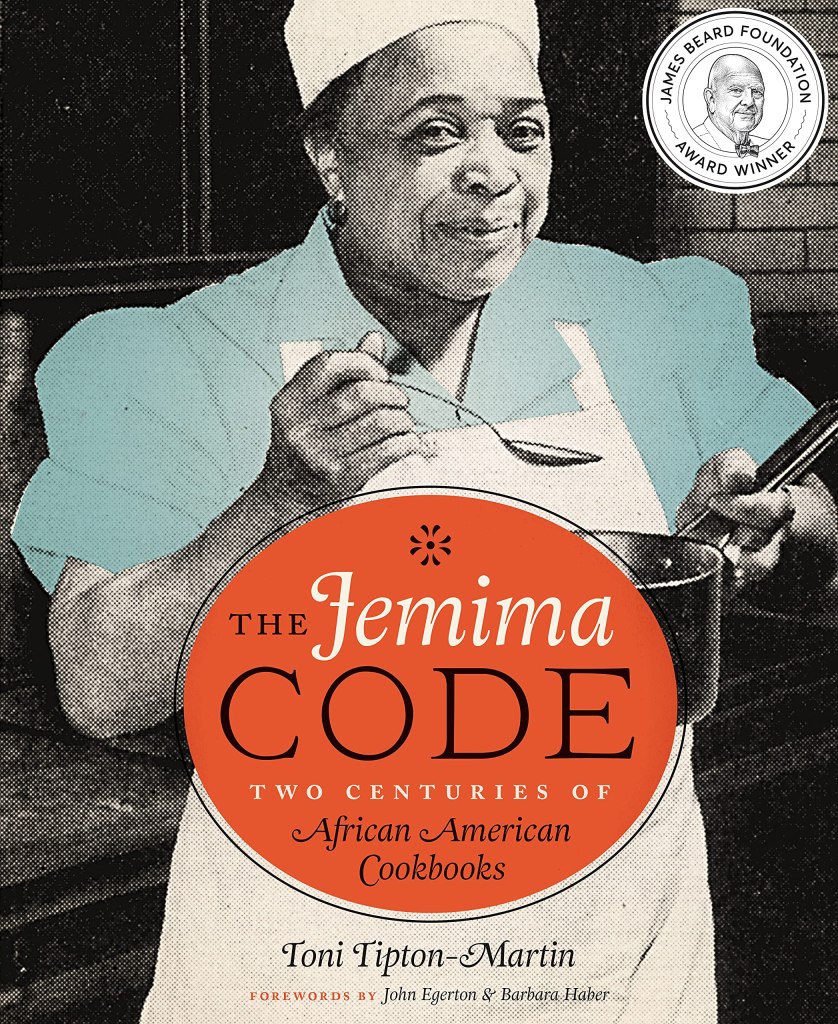

At the age of 74, Smith opened her first restaurant, Lucille B. Smith's Fine Foods Inc., which counted Eleanor Roosevelt and Joe Lewis among its customers. Austin food historian Toni Tipton-Martin highlighted Smith's deeply influential contributions to black culinary entrepreneurship in Texas via her blog, The Jemima Code, especially because Smith's career is a direct counterpoint to the degrading stereotypes common in Aunt Jemima's pancake syrup and Uncle Ben's rice. (Tipton-Martin's copy of Smith's cookbook is kept in a fireproof safe under lock and key.) Despite the immense popularity of her hot roll mix, Smith was almost never credited, and certainly never compensated, for her contributions to commercial culinary ventures in American history.

The Jemima Code

Chris Williams, Smith's great-grandson, was only 6 when his great-grandmother died, but he has vivid memories of chatting with her "for hours about anything and nothing." Smith died in 1985 at age 92 and is buried in Haltom City, just a few miles from downtown Fort Worth.

Her legacy lives on, of course, at Lucille's in Houston, and has even incorporated Top Chef luminaries: Season 18 finalist Dawn Burrell is currently developing her own restaurant concept, titled Late August, under the Lucille's umbrella of restaurants and nonprofit food initiatives in the Houston area. It is clear that Lucille B. Smith is to Texas what Edna Lewis is to the American South.

READ MORE: 11 Romantic Restaurants in Houston To Wine & Dine in Style