Marty Stuart has spent most of his life on the road. That may be true of most country legends of Stuart's stature, but you'd be hard pressed to find an artist who's logged more hours on tour buses than the Mississippi-born artist, who joined Lester Flatt's band when he was just 13. So it's fitting that the Country Music Hall of Famer wrote the majority of his forthcoming album Altitude — a collaboration with longtime band The Fabulous Superlatives — while on tour. (The album will be out May 19 via Snakefarm.) Stuart found inspiration for the record, a high-flying cosmic country joyride, during his 2018 tour with longtime heroes and The Byrds co-founders Roger McGuinn and Chris Hillman, who reunited for the 50th anniversary of their Sweetheart of the Rodeo album.

Videos by Wide Open Country

Ahead of the release of the album and the premiere of the new video for "Country Star," Wide Open Country caught up with Stuart to talk about his new album, how The Byrds' Sweetheart of the Rodeo changed his life, his 30 years as a Grand Ole Opry member, and what Minnie Pearl had to say about his pants.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

You've called Sweetheart of the Rodeo the blueprint for your musical life. When was the first time you heard the record? How did it impact you?

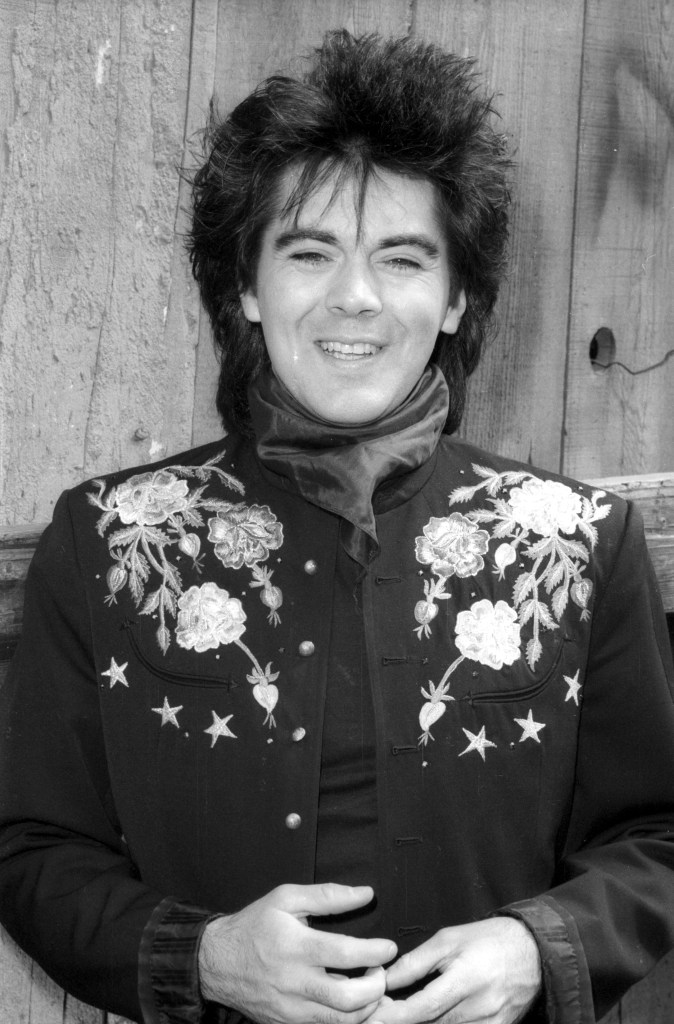

Alysse Gafkjen

I really don't know where that song came from. It's just one of those that rolled in out of the sky. It was just a bunch of hocus pocus imagery set to a Memphis beat. I think it was an attempt at taking one thought and making a song revolve around it.

I liked it from the get-go when the line appeared on the page, it said ... "the Archer shot an arrow/ went sailing through the woods and the arrow hit the dirt and said, well, you ain't no Robin Hood" ... [I thought] That's pretty good. Keep going. [Laughs]

"The Angels Came Down" is such a beautiful song. What inspired that?

We were coming home to a tour, and we were passing through Memphis. ... If you look to the left when you're coming through Memphis on the way back to Nashville, there's St. Jude Hospital for Children. I almost could tangibly see angels sitting all over that building that day. I just saw a legion of angels around that building. And I thought about times in my life where there was nothing but darkness. I was at the end of the road, out of aces, you know, there were no tricks left up my sleeve, but mercy appeared and the angels came down. The song was so simple, and it came so fast and it was so true. And those are usually the ones with the most power.

This is one of the last albums that [Country Music Hall of Famer and legendary keyboardist] Hargus "Pig" Robbins played on. What does it mean to you to have him on this record?

Well, he was on the very first session I recorded in Nashville in 1973. [When I played with Lester Flatt's band] Pig was on that session, and he was on Connie's [Smith, country legend and Stuart's wife] first hit. And wonderfully strange enough, the last song he ever played on was a Connie Smith song. But "Altitude" was one of the last songs that he played on. And Pig was one of those kind of people — I had so much reverence, love and respect for him, and the band felt that way, too. When Pig walked into a room, things just got better, just simply by way of his presence, because he had been a part and such a master architect of so many boulder-size recordings in country music.

Well, I started playing there on that show when I was 13 with Lester Flatt's band. Roy was regarded as the king of country music, and Minnie Pearl was probably the grande dame of the Opry. ... When I started making records on my own, I kind of took my own version of tradition and did a different spin on it. It was a little louder. It was a little more boisterous, [it had] a little more rock 'n' roll on it than they probably were accustomed to. So it was important to me to have their blessing. And Mr. Acuff gave it to me. ... Minnie Pearl was kind of bedridden at home at that time in her life.

I found out from Judy Seale, [Minnie Pearl's] manager, that she loved white roses. I think it was either 50 or 75 white roses I went walking in the room with when I was granted an appointment to see her. I walked in and she said, "Oh, look at those tight pants." [Laughs]

American country comedian and singer Minnie Pearl (1912-1996) poses in the 1970s. (Photo by Archive Photos/Getty Images)

It was a wonderful visit. I think that song of mine she had heard called "Hillbilly Rock" — that was the first hit. And so the only thing that she had to say ... is, "I wish you would reconsider that word hillbilly." I said, "Yes, ma'am." She said, "We've worked so hard to get beyond that, and I feel like it's not the best word to use," and I went, "Yes ma'am, I totally respect and understand." That's the kind of wisdom you don't get from just anybody. That's why she was Minnie Pearl.

Photo by Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

I remember the way the room felt. It was hot. You could smell popcorn. You could feel people's sweat. You could feel people's hearts. I couldn't believe I was there. I mean, if you grow up in the South, especially if you're me growing up in the South, everybody on that show felt like family to me before I ever shook anybody's hand. I always felt like I belonged to that show. I just longed to be a part of it. I just remember we were about to go out on stage. Lester looked at me and Roland White and he said, "Y'all do that song you did last week." And I went, "What!?" I thought I was just gonna be a tag-along, and all of a sudden I find myself [about to be] on the show.

I remember the curtain coming up and there it was: this show that I'd heard for so many years. ... I don't remember if it was a fast song or a slow song we played, but I just knew I was there. When my time came to play, when he introduced me, I just remember thinking: Get this right, because your mama and daddy and Jennifer, my sister, they're listening down in Mississippi. It's a 50,000-watt beam, and this should be done right. So I did the best I could. When I got through playing and singing with Roland, the crowd just kept going crazy. I thought I'd done something wrong. I looked at Lester. I said, "What do I do?" He said, "Do it again." [Laughs] After the end of the encore, I spun around to walk off the stage, and there stood Roy Acuff and his band and Tex Ritter and those Opry staff musicians. People had gathered around to see what the fuss was about. They all welcomed me. I couldn't believe it. It was a great way to start.

You and The Fabulous Superlatives [Kenny Vaughan, Harry Stinson and Chris Scruggs] were inducted into the Musicians Hall of Fame last year. What did it mean to you to be inducted alongside them and share that moment with them?

Terry Wyatt/Getty Images

That's what it was about — to share it with them. That meant the most to me because they deserve it. They've lived their entire lives dedicated to their music, dedicated to their craft. They're more than just, you know, standard-issue pickers. Those guys are teachers, they're inspirational characters. They're becoming folk heroes. And to stand there next to 'em and know that we have carved this out — night after night, handshake by handshake, song by song, good show, bad show — without the assistance of anything except God Almighty and talent ... it was a wonderful thing to share with those guys.

In addition to your career as a musician, you're also an accomplished photographer. How did you become interested in photography?

My mama. [Laughs] My mama is my favorite photographer. My mama's 89 years old, and she's still my favorite photographer. She had such a gift. It didn't matter what kind of camera she had — she could be frying chicken, and if the kids were doing something, she'd just pick up a camera with one hand and go click. And all of a sudden you had this instant classic that was a family treasure, but it was also kind of formal and beautiful. There was an accessibility, and it was from Mama's perspective and from Mama's heart. So I was just always drawn to photography. I loved poring over her photographs as a little kid. My uncle had a portrait studio in Philadelphia, Mississippi. Photography was just part of the atmosphere around the house. When I first went on the road and the first time I went to New York City, I went into a bookstore in the Village, and there were some beautiful photographs up on the wall of this bookstore that were taken by a jazz bass player named Milt Hinton.

Milt, from what I perceived, took his bass in one hand and his camera in the other, and he had unparalleled access to the family of jazz. His pictures kind of reminded me of my mama's pictures. They were formal, but yet there was an informal quality. They had a family-like quality to them. I walked outside of that bookstore and called home to Mississippi and asked my mom to send me a camera. She found one and put it in the mail and sent it to me up in Nashville. And I proceeded to terrorize everybody in the world of country music with my camera. [Laughs]