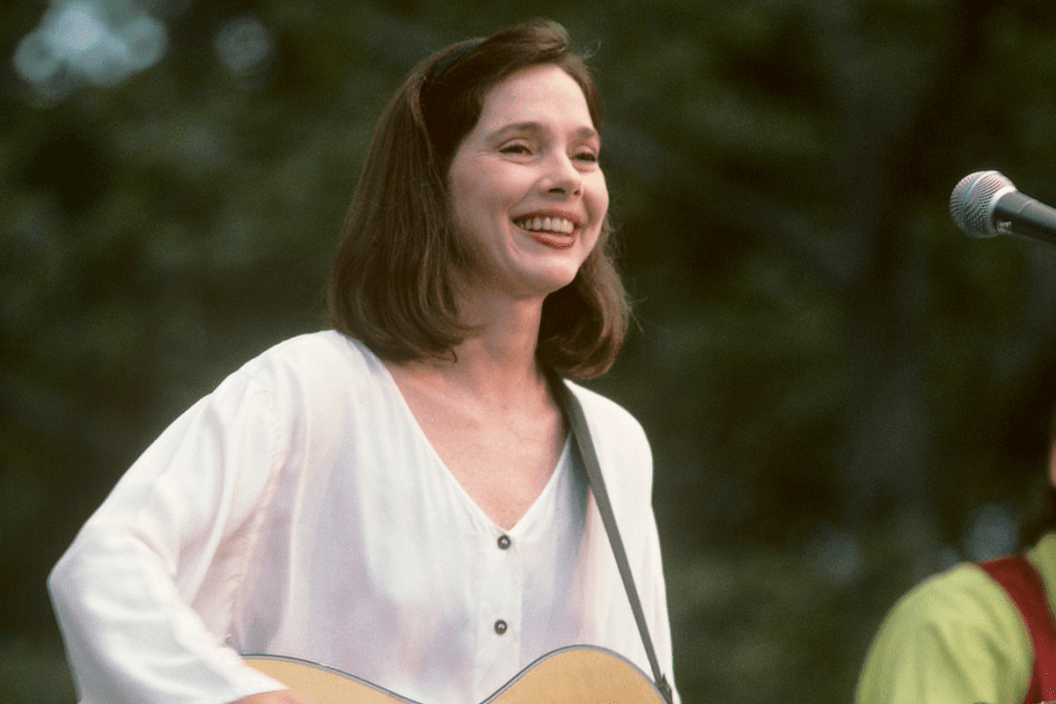

With her tiny bow of a mouth, ashy hair and heart-shaped face, Nanci Griffith seemed more Dust Bowl sweetheart than the erudite songwriter with a lean finger on the pulse of the human condition. Romantic, but clear-eyed, she told people's stories with an attention to detail that would've made her literary heroines Eudora Welty, Carson McCullers, Flannery O'Connor and Willa Cather proud.

Videos by Wide Open Country

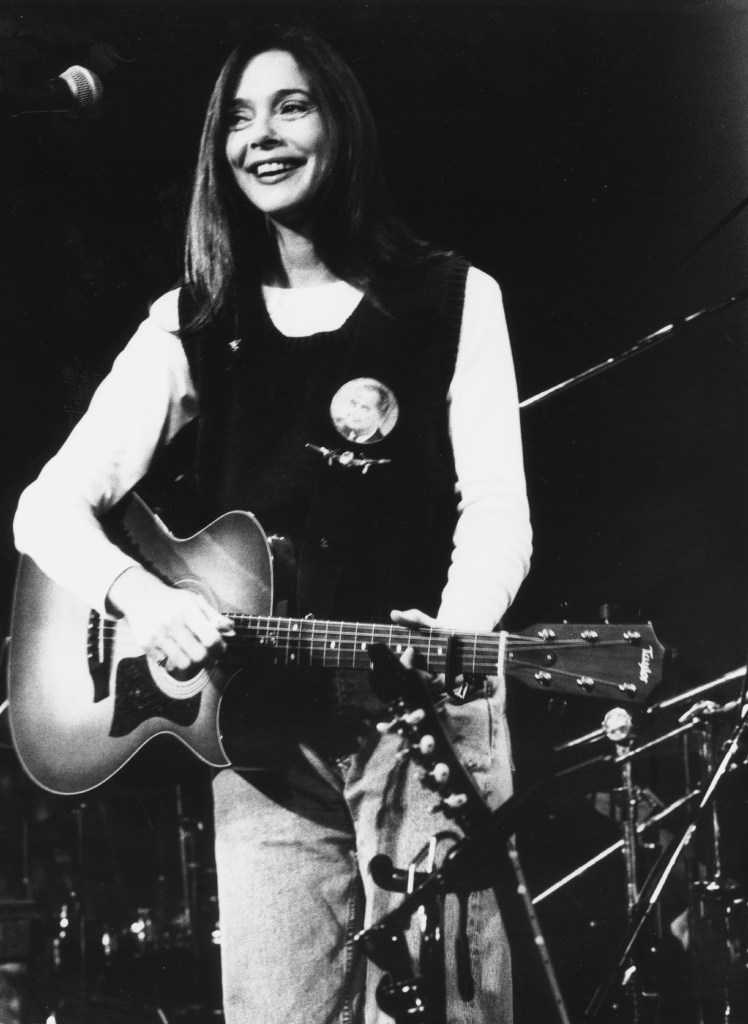

Photo Paul Natkin/Getty Images

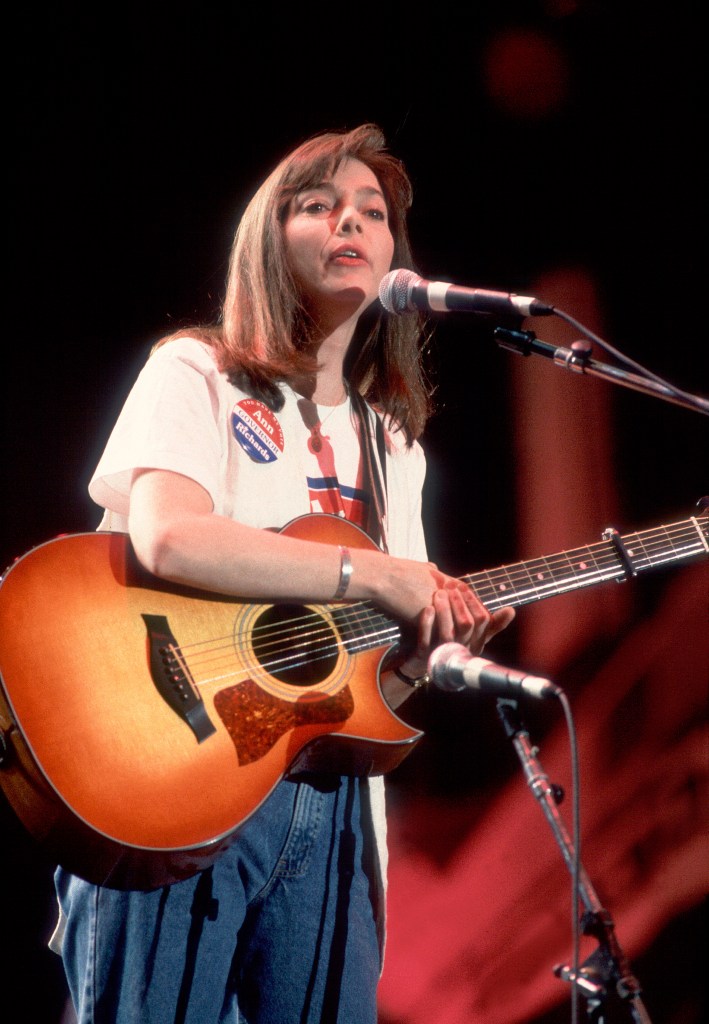

Born in Seguin, Texas, raised playing Austin's coffee houses as a teen, Griffith emerged with an ether-like singing voice that could grow serrated, even worldly in the knowing places. She called it "folkabilly," to honor her inspirations, and moved from independent folk/bluegrass label Philo to MCA Nashville filling out uberproducer's career-defining cred-quartet of Steve Earle, Lyle Lovett and Patty Loveless. Perhaps too -- or not enough -- country for radio, she elevated again to Universal in California, knocked off some of the twang and made definitive adult alternative albums before moving to Nonesuch where her Grammy-winning homage Other Voices, Other Rooms - and its sequel A Trip Back To Bountiful - paired her with even more artists she respected. Griffith's gift was how she distilled not just life, but her influences to honor what was - and create something of her own. Other Voices homaged Kate Wolf, Woody Guthrie, Townes Van Zandt, Solomon Linda, Bob Dylan and Janis Ian; her "Speed of the Sound of Loneliness" - with its Wim Winders' "Wings of Desire"-inspired video co-starring John Prine - was more a lullabye of compassion than a requiem for a dead love.

An international favorite and regular on The Late Show with David Letterman, 1994's Flyer marked the ultimate convergence of the world she'd created. Co-produced by r.e.m's Peter Buck, the beyond genre work showed the breadth of her reach, featuring guests Mark Knopfler, U2's Adam Clayton and Larry Mullen, Jr, Emmylou Harris, the Chieftains, Widespread Panic's Dave Schools, the Indigo Girls, Counting Crows' Adam Duritz and the Cricketts, while writing with Country Music Hall of Famer Harlan Howard and "From A Distance" writer Julie Gold.

Photo by Sherry Rayn Barnett/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Here are the 10 best Nanci Griffith songs.

"Not Innocent Enough," The Loving Kind, 2009

Nanci Griffith, in true folkie tradition, worked from a strong sense of social justice. The Loving Kind's title track was inspired by the 1967 Supreme Court decision on Loving v Virginia to strike down miscegenation laws. More modern and more urgent, "Not Innocent Enough" took a first person turn on death row inmate Philip Workman, who was executed in spite of new evidence suggesting innocence. Conflating circumstances, blurred agendas and the relativity of "guilty," the song features a spoken word section from Workman on the coda.

"Late Night Grand Hotel," Late Night Grande Hotel, 1991

A slight accordion wheeze, a piano, then the drums tumble as Griffith's more growling bottom sweep through a song built on what love can be, but also owning one's independence. For a woman who'd given her life to the road, it's the natural habitat of a romantic and a poet balancing the notion of love with the need for travel and healing. Stark, invoking Greta Garbo. It's the part no one ever admits.

"Ford Econoline"/"Lookin' for the Time (Working Girl)," Lone Star State of Mind, 1987/Last of the True Believers, 1986

Hard scrabble women might seem like unlikely heroines for the songwriter who was equal parts Willa Cather and Eudora Welty. Yet the hard strumming "Ford Econoline" celebrates foik music pioneer Sorrels, while the guttural roar of the slapdown chorus of "Lookin' for the Time" is a sex worker's rejoinder to a john who can't make up his mind.

"Trouble In The Fields," Lone Star State of Mind, 1987

Raised on the folk of Caroline Hester and Rosalie Sorrels, Griffith reached into the hard times working class reality of people who existed in a world of more primitive realities. Whether sharecroppers, migrant workers or family farmers - this appeared during the initial wave of Farm Aid and "keep family farmers on the farm" activism, "Trouble In The Fields" captures how hard this work is, the toll extracted and the strength it takes to face the days.

"There's A Light Beyond These Woods," There's A Light Beyond These Woods, 1978

Young girls, big hope. With that voice that sounds like Alice in Wonderland on the brink of adulthood, Nanci Griffith ponders to her friend that there must be more. Long before the world knew who the young songwriter with the heart-shaped face was, people around Texas absorbed her worldly innocence and filigreed acoustic guitar. An artist to be noticed emerges.

"Gulf Coast Highway," Little Love Affairs, 1988

Reading like a Larry McMurtry short story, "Gulf Coast Highway" was a life-spanning postcard from the Lone Star State featuring Mac McAnally as the other half of a couple living in a small house along Highway 90. Stately in how it moves, this is a simple song of love that endures strung on the imagery of life across time, each year measured with the coming of "some sweet blue bonnet spring."

"Drive-In Movies & Dashboard Lights," Storms

Suddenly the world knew Nanci Griffith, whose folkabilly revolution charmed David Letterman and created a haven for bookish young women everywhere. Rather than stay where she was, Griffith tapped producer Glyn Johns for the album that made the instruments more electric, crisper and sharper. A stark, alternative-leaning record, "Drive-In Movies" was a time capsule invoking a girl's life in the Lone Star State, 1969 that fell into the cliché expectations Griffith had fled. Like Peter Bogdanovich's Last Picture Show, this endures as not-so-innocence-turning-empty.

"It's A Hard Life Wherever You Go," Storms, 1991

A late night conversation between Griffith and a Belfast cab driver opens the striding folk song, as he explains the odds a kid on the corner is up against. The second verse finds the drawling vocalist in a Chicago cafeteria where she encounters a racist man poisoning his children with hatred.

"Cafeteria line in Chicago/ The fat man in front of me/ is calling black people trash to his children/ He's the only trash here I see," Griffith sings. "And I'm thinking this man wears a white hood/ in the night when his children should sleep/ But they'll slip to their window and they'll see him/ And they'll think that white hood's all they need."

Stark. Sobering.

"Anything You Need But Me," Flyer, 1994

Having had more than enough, "Anything" shows a woman leaving without malice, wishing the now former love well - but being clear "done is done." Sprightly, the acoustic guitar notes gleam against her the little girl part of her voice - chosen perhaps to remind the cad what he's broken - Griffith offers dignity while drawing a line and setting a clear boundary. Walking the line has never been so supple or so easy, which is anything but what most people find this kind of moment to be.

"Love at the Five & Dime," Last of the True Believers, 1986

Innocence was never as sweet or compelling. Live Griffith showed audiences the little guitar "ting" buried in the track that recalled the sound of the elevator at the Woolworths where she changed buses growing up. More importantly, Rita with the chestnut hair got to grow up and live a fairy tale love affair with a music man who'd retire, growing old together.

Happily ever delivered with folk purity, a little bit of sparkle and the wrinkled nose pleasure that Griffith found in particularly well-sketched stories. Believers brought the major labels. "Five & Dime" gave Kathy Mattea her first real hit record. For fans, though, it was the essence of an artist who would captivate people around the globe for almost four decades.