Five people died. 197 people in 35 states were infected; 89 of those people were so sick they needed hospitalization, and 26 of those people developed hemolytic uremic syndrome, a type of kidney failure. We know what made them sick — eating romaine lettuce from Arizona's Yuma growing region contaminated with the E. coli bacteria — but we still don't know exactly how the outbreak started or spread. The growing season is over now, which means the romaine lettuce E. coli outbreak is also over, but it also means any chance of tracing the E. coli outbreak to a specific farm, processor, or distributor has most likely passed.

Videos by Wide Open Country

While the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is working to find the cause of the outbreak, 10 consumer and food safety groups think there is more the government agency could be doing, including using the rules designed to help track high-risk food that Congress passed into law as part of the 2011 Food and Safety Modernization Act. The groups recently sent an open letter to Scott Gottlieb, the FDA commissioner, asking for new steps to be taken to protect American consumers.

The FDA is responsible for our nation's food safety. They work with producers to issue recalls when necessary and with the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to track outbreaks of diseases like E. coli and salmonella.

What happens in a food recall?

Food recalls happen fairly frequently. Some of them happen because an incorrect ingredient was used, which could make the product unsafe for those with allergies or certain medical conditions, or the package was mislabeled and didn't match the product inside the box. Some recalls are about product where a consumer found tiny pieces of plastic or glass in the food.

And then there are the recalls where the food is contaminated with some kind of bacteria. In addition to the romaine recall this year, we've seen a massive recall of eggs contaminated with the Salmonella bacteria. Smaller recalls have been issued for beef and sausage.

The two major food recalls this year illustrate how difficult tracking food-borne illness can be. In the case of the egg recall, the FDA and CDC were able to fairly quickly trace the outbreak to one particular farm in North Carolina and issue a recall for any eggs that came from that one farm. But with the romaine, the FDA hasn't been able to pinpoint one farm, processor, or distributor as the ground zero for the outbreak and so their advice to the public was simply to stop eating romaine lettuce.

Why don't we know the point of origin?

Part of the difficulty of tracing the source of the contamination is that it happened as a wide-spread multistate outbreak. While the majority of people affected by the contaminated romaine were in Pennsylvania and California, where one death was reported, a total of 35 states reported cases of E. coli infections. The four other deaths were reported in Arkansas, Minnesota, and New York. Some of those reporting symptoms noted that they didn't eat lettuce, but they had close contact with people who did.

To understand why it's sometimes difficult to find the origin of food contamination, let's look at how the FDA follows an outbreak, starting all the way back at the grocery store. You buy the lettuce during your regular shopping trip on Saturday morning, but the expiration date on the bag isn't for six or seven days so you don't worry about eating it immediately. When you finally do eat the lettuce on Wednesday, everything seems fine. Because E. coli symptoms typically show up three to four days after being exposed, you don't get sick until the weekend.

You probably don't think it was the lettuce that made you sick. Maybe it's just the cold your kid brought home from school or that other bug that's been going around. It could have been something you ate, but who knows what? And if you're a healthy adult, you probably recover within a week without any additional problems.

But if you do get sick enough to go to the hospital, it's probably a few days after you first get sick. Now we're almost a week and half or more after you bought the lettuce. Chances are, that lettuce isn't is your fridge anymore because you've eaten all of it or thrown it out after it went bad.

Once the hospital knows why you're sick, they send a report that they have a patient with E. coli to public health officials, including the CDC. When the CDC sees more than a few cases, they work with the FDA to trace the origin of the E. coli. By now, it could be two weeks after you purchased the lettuce (and three or four weeks after the lettuce was harvested), no one has the original product or package. Because of the short 21-day shelf life of lettuce, it's harder for the government to trace the origin of contaminated lettuce.

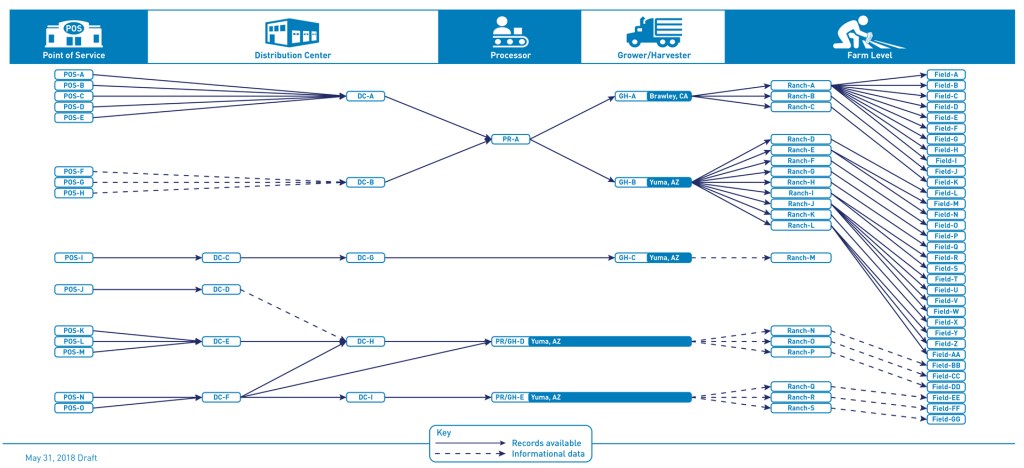

So far, all the FDA has been able to to do is figure out what they know didn't happen. They've determined the cause wasn't as simple as, for example, one farm using unsafe harvesting techniques or a processor not washing the lettuce properly before packaging. You can see in this diagram of tracebacks that there is not a clear line going back to one point in the romaine lettuce E. coli outbreak.

According to a FDA blog post:

"It [the evidence] says that there isn't a simple or obvious explanation for how this outbreak occurred within the supply chain. If the explanation was as simple as a single farm, or a single processor or distributor, we would have already figured that out. The traceback diagram does show us that the contamination with E. coli O157:H7 was unlikely to have happened near the end of the supply chain (such as at a distributor) because there are no common distributors among the places that received and sold or served contaminated lettuce. The contamination likely happened at, or close to, the Yuma growing area."

What happens next?

The 10 organizations that signed the open letter to the FDA think the inability to trace where the lettuce came from is exactly the point. In the letter, they point out the advances in technology that should make it easier to trace a product's path from field to plate.

"Current technology makes it possible for retailers to track and trace products with extraordinary speed and accuracy. Retailers using advanced technology, such as blockchain, now report they can identify the origin of certain produce shipments in as little as 2.2 seconds. Given these advances, it is no longer acceptable that the FDA has no means to swiftly determine where a bag of lettuce was grown or packaged."

They are asking the FDA to finally institute the rules made possible by the Food and Safety Modernization Act passed by Congress seven years ago, including establishing better record keeping requirements for high-risk foods, or foods that have more potential to carry bacteria like E. coli and Salmonella.

The FDA has not yet publicly responded to this call to action, but perhaps the difficulty in tracing this particular romaine lettuce E. coli outbreak will convince them to work with the food industry to take additional steps in protecting our food system.