Wheeler Walker Jr., the profanity-spouting and country-singing alter ego of comedian Ben Hoffman, kicks off The 2022 Comeback Tour on Thursday (April 14) at Nashville's Ryman Auditorium.

Videos by Wide Open Country

At some point since Walker's 2016 recording debut, you've likely made up your mind about the polarizing character and his lewd lyrics. Some exalt his music as free expression from an "outlaw" point of view. Others either shunned the gimmick all along for being sophomoric or lost interest once the shock factor of his first album wore off.

Walker's further defined his persona through social media and on podcasts by frequently mocking Sam Hunt, Florida Georgia Line and other popular artists he's deemed as the opposite of "real country music." Back in March, Walker went as far as picketing FGL's exhibit at the Country Music Hall of Fame before being escorted off the property by security. Even if his one-man protest was a publicity stunt to promote the album Sex, Drugs & Country Music (out April 15 via Pepper Hill Records/Thirty Tigers), Walker's take on FGL will surely elicit more shouts of "amen" from the mother church's pews than eye-rolls because of common misconceptions about country music history.

Based on both the message and means of Walker, it makes historic sense that he'd kick off his tour at the Ryman. After all, tired authenticity debates and crowd-pleasing comedic performances have long been a part of country music, so why not bring a conversation starter for both to one of the genre's most hallowed stages?

"Real Country Music"

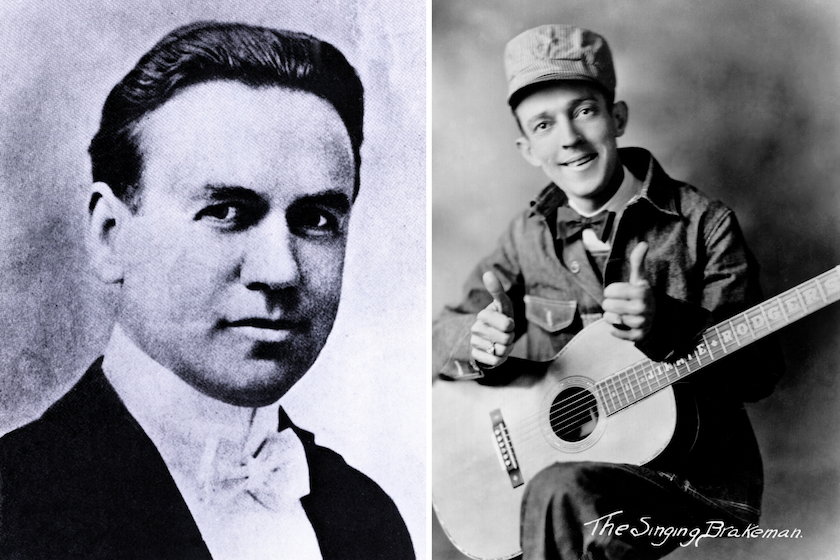

Early country music influencers Vernon Dalhart and Jimmie Rodgers (GAB Archive/Redferns and BMI/Michael Ochs Archives/GettyImages)

The practice of well-rounded entertainers adopting country singer personas dates back nearly 100 years. Vernon Dalhart, whose 1924 version of "Wreck of the Old 97" became country music's first million seller, was one of over 100 pseudonyms used by Marion Try Slaughter, a classically-trained Texan who'd initially dreamed of becoming an opera singer. Its success inspired the 1927 Bristol Sessions, which broke the career of former railroad worker Jimmie Rodgers, the "father of country music."

Rodgers wears that crown because the nascent recording industry promoted what became known as country music in such a way that some artists got judged by the general public as authentic or hardcore while others got written off by a portion of the audience as more manufactured or soft-shell. The late sociologist Richard A. Peterson covers the origins of pop-country complaints thoroughly in his aptly-titled 1997 book Creating Country Music: Fabricating Authenticity.

The history of the Grand Ole Opry, a show synonymous with the Ryman (its home from 1943 to 1974), further proves that authenticity debates predate modern opposition to so-called "bro-country." For example, professionally-trained trio The Vagabonds starred on the Opry in the 1930s before the more rustic-sounding Roy Acuff shifted the program's focus back to a lineage of tradition-bound regulars that began in the 1920s with banjo picker and jokester Uncle Dave Macon.

In more recent times, hardcore versus soft-shell has played out in different terms: the Bakersfield sound versus the Nashville sound in the '60s, outlaws versus Olivia Newton-John in the '70s, neo-traditionalists versus Urban Cowboys in the '80s and so on. Even '90s country faced harsh criticism in its time, with alt-country artist Robbie Fulks' 1997 song "Fuck This Town" blasting acts now widely perceived as the last big-label bastions of tradition for recording "soft rock, feminist crap."

As far as protesting goes, country embracing other corners of popular music spurred picketing in 1974 when the Pointer Sisters, singers of the undeniably honky-tonk hit "Fairytale," debuted on the Grand Ole Opry. Five years later, Porter Wagoner invited James Brown to perform on a Saturday night Opry broadcast. Cast members voicing their opposition to the press included Ernest Tubb, who'd ruffled gatekeepers' feathers in the '40s by introducing electric guitar to country music.

A near-century of pop-country crossovers aside, much more valid complaints can be made that the sameness nowadays of country radio, major label rosters and other typical avenues to commercial success limit sonic variety and racial and gender identity diversity in the mainstream.

Walker continually shows up this flawed system by succeeding in spite of it. Consecutive Dave Cobb-produced albums (2016's Redneck Shit and 2017's Ol' Wheeler) not only topped the comedy charts. Both became Top 10 country albums without Music Row backing— and with lewd songs that by design weren't radio-friendly unit shifters. His third album, WWIII (2018) peaked at No. 20, further proving a point already made by Walker confidant Sturgill Simpson and others: the commercial potential of artists intentionally outside of the Nashville norm is no joke.

Country Comedy

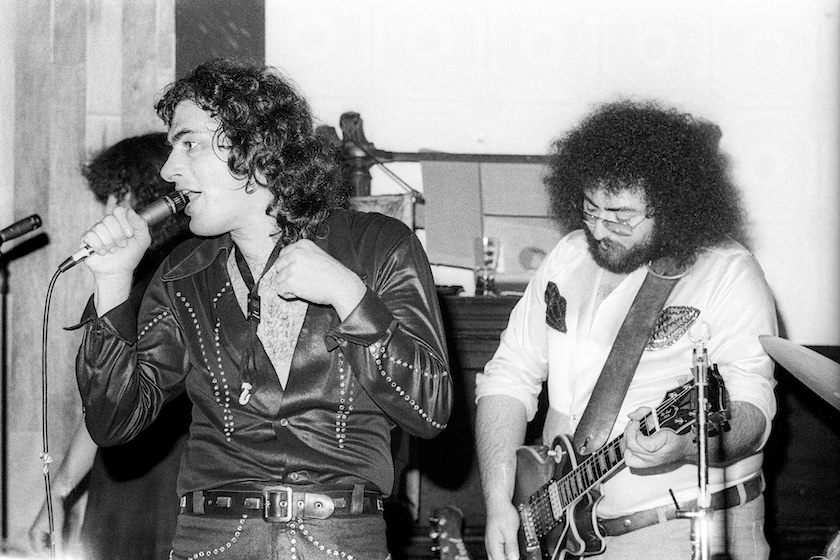

Nick Chavin aka Chinga Chavin and guitarist Johnny Erokan perform with Country Porn on April 1, 1978 in San Rafael, California. (Photo by Ed Perlstein/Redferns/Getty Images)

However you may feel about Walker's message, his means remind us of the long history of country comedians that have laughed with, not at, their audience.

Just as country music itself has long been a "big tent" that incorporates enough influences and sounds to keep authenticity debates raging, the term "country comedy" has never fit a narrow definition. Indeed, it can describe everything from the aw-shucks shtick of Minnie Pearl and the parody songs of Cletus T. Judd to the self-depreciating stage banter of Mel Tillis and the surreal brilliance of Shel Silverstein, writer of Johnny Cash's "A Boy Named Sue."

Of course, artists that were outright vulgar instead of playfully suggestive or unapologetically cornball typically found themselves outside of such straight-laced institutions as the Ryman, where Walker will thrill fans with the less-than-subtle "Drop 'Em Out."

Chinga Chavin pioneered x-rated twang with his 1976 album Country Porn. When major retailers refused to carry Walker's music, he built an audience through the internet and independent record stores. Chavin faced a steeper hill, relying mostly on ads in Penthouse magazine to sell a sexually-explicit album. Chavin composition and Merle Haggard send-up "Asshole From El Paso" escaped obscurity when it entered the setlist of another infamous outsider, Kinky Friedman.

Forty years after Chavin's potty mouth placed him on the fringes of the mainstream, digital streaming and other modern conveniences paved a clearer path for Walker to conquer the charts and the Ryman stage with comparably graphic lyrics.

In short, though critiques of country authenticity date back nearly 100 years, high-profile opportunities for an intentionally hard-to-market dissenter like Walker (comedy bit or not) mark something refreshing for a genre that's hardly above reproach.